Culture is a part of our DNA, especially for those who trace their lineage to the culturally rich land of Bharat. They carry it with them wherever they go. Just like a plant uprooted and replanted, sheds a few leaves before it grows new ones, Indian diaspora is also embracing its root culture with renewed enthusiasm. They have recreated or replicated the Tirthas of their Ishta Devatas and Kula Devatas so that they can carry on with the periodic rituals and traditions close to where they are. Over time, when there are substantial numbers of diaspora in a region, and they are economically well settled, they start building their temples and start creating a microcosm of the Tirtha ecosystem of their motherland. These Tirthas help the community bond together over shared festivals with a multitude of cultural elements like food, dressing up, music, dance, rituals roughly based on the Indian Panchang.

Replication of Tirthas in different parts of the world depends on the people from which region of India dominate in terms of numbers or which devotees act based on their devotion.

Some of the examples of this are recreation of Ayodhya as Ayutthaya in Thailand, grand celebration of Thaipusam in Singapore, Ganga in Trinidad and Tobago. Batu Caves in Malaysia replicate the hill temples dedicated to Kartikeya in South India. A new Jagannath temple is being built in London after replicating in many cities across India. A series of new Swaminarayan and ISKCON temples are being built across the world to cater to Hindus living there. We also see recreation of those tirthas that are currently outside the political boundaries of India in India like Hinglaj Mata at Mata Na Madh in Gujarat or very recently Sharada Peetha at Teetwal on the Indian side of the Krishna Ganga River.

The paper will explore the invisible threads that bind the Indian Diaspora to their motherland through culture, religion and rituals.

——————————————————————————————————

Culture is that invisible thread that cannot be seen but can only be experienced. It is ingrained in our DNA, through the genes we inherit, through the small family rituals that nurture our growing up years. They get re-enforced when they are repeated at a community level. These small rituals and traditions are how migrants stay rooted in the culture of their ancestors.

Those who trace their lineage to the culturally rich land of Bharat, they carry it with them wherever they go. Just like a plant uprooted and replanted, sheds a few leaves before it grows new ones, Indian diaspora is also embracing its root culture with renewed enthusiasm. They have recreated or replicated the Tirthas of their Ishta Devatas and Kula Devatas so that they can carry on with the periodic rituals and traditions close to where they are. Over time, when there are substantial numbers of diaspora in a region, and they are economically well settled, they start building their temples and start creating a microcosm of the Tirtha ecosystem of their motherland. These Tirthas help the community bond together over shared festivals with a multitude of cultural elements like food, dressing up, music, dance, rituals roughly based on the Indian Panchang.

Relocation of Tirthas also shows the migration pattern from certain parts of India to certain parts of the world. While individual migrants mostly restrict their religious and cultural activities to their homes and private spaces. However, when the diaspora becomes a community rooted in the same or similar religio-cultural ethos, they slowly start strengthening that ethos by coming together to celebrate them and to ensure their continuity of the tradition for the next generations. There are also cases of replication of Tirthas that have fallen out of Indian political boundaries and their replicas have been created in India, keeping the memory of the deity and its tradition alive.

Let us look at some examples of recreations of Tirthas chosen from different parts of the world, from different times in history and with different reasons depending on the status of immigrants that varies from indentured laborers to economic migrants.

Recreation of Ganga in Mauritius

Ganga Talao, commonly known as Grand Bassin, is a crater lake situated at approximately 1,800 ft above sea level in the Savanne district of Mauritius. Recognized as the most sacred Hindu site on the island, it has emerged as one of the most important Hindu pilgrimage centers outside India. It exemplifies the successful transplantation and adaptation of North Indian devotional traditions among the descendants of 19th-century indentured laborers.

In 1897, Pandit Giri Gossagne Napal, a priest from Triolet in northern Mauritius, experienced a visionary dream revealing that the waters of the lake—then known locally as Pari Talao—were mystically connected to the Ganga in India. Accompanied by Pandit Mohanparsad, he undertook the first recorded pilgrimage to the lake in 1898, performing ritual snana and puja. Bubbles rising from the lake bed were interpreted as a divine manifestation of the Ganga’s presence. This foundational event transformed an obscure volcanic lake into a tirtha sthala.

The formal consecration took place in 1972 when Pandit Rajcoomar Jhurry brought Ganga water from Gomukh, the source of the Ganga at Gangotri in Himalayas, and merged it with the lake, thereby establishing an ontological link with the Indian river. Subsequent decades saw infrastructural development, facilitated by state land grants and private donations. By the late 1990s the lakeside complex added temples dedicated to Shiva, Durga, Hanuman, Ganesha and Lakshmi. A 33-metre Mangal Mahadev statue of Shiva inaugurated in 1998 is the most visible landmark.

The formal consecration took place in 1972 when Pandit Rajcoomar Jhurry brought Ganga water from Gomukh, the source of the Ganga at Gangotri in Himalayas, and merged it with the lake, thereby establishing an ontological link with the Indian river. Subsequent decades saw infrastructural development, facilitated by state land grants and private donations. By the late 1990s the lakeside complex added temples dedicated to Shiva, Durga, Hanuman, Ganesha and Lakshmi. A 33-metre Mangal Mahadev statue of Shiva inaugurated in 1998 is the most visible landmark.

The annual Maha Shivaratri festival takes place at Ganga Talao. On the eve of the new moon in the Hindu month of Magha (February/March) or Magh Krishna Chaturdashi, several hundred thousand devotees—frequently exceeding 400,000 —undertake barefoot yatras from their villages to the lake, carrying ornate kanwars (wooden arches with pots at the end). The pilgrimage spans three to four days and culminates in darshan and abhisheka of Shivalinga with lake water, and ritual snana . The lake’s water is regarded as equivalent in sanctity to the Ganga itself. Devotees use it for their pujas as well as for Asthi Visarjan or the immersion of cremated remains.

For Mauritian Hindus, Ganga Talao is a sacred centre— a symbol of cultural continuity for the Indo-Mauritian community, which constitutes approximately 68 % of the national population. The state recognizes Maha Shivaratri as a public holiday. Thus, Ganga Talao illustrates a distinctive process whereby a geographically remote volcanic lake has been indigenised as an extension of the Ganga, sustaining a vibrant tradition of devotional practice among the Indian diaspora for over a century.

Thaipusam in Southeast Asia

Thaipusam festival is observed on the full-moon day of the Tamil month of Thai (January–February) when the Puṣya nakshatra is ascending. The festival is dedicated to Murugan also known as Skanda or Kārttikeya, the warrior son of Shiva and Parvati. The festival’s contemporary mass-public form with urban processions is largely a product of nineteenth and twentieth-century Tamil diasporic communities in colonial Southeast Asia.

The Thaipusam story describes Parvati giving the vel or the sacred spear to Murugan to vanquish the asura Sūrapadma on the day of Thai Puṣya. In Tamil Nadu, the festival is traditionally celebrated at the six sacred abodes (Arupaḏai Vīḏu) of Murugan – Palani, Tiruttani, Swamimalai, Tiruchendur, Tirupparankunram, Pazhamudircholai.

The large-scale public celebrations however, emerged among Tamil labour migrants in British Malaya and the Straits settlements from the late nineteenth century onward. The institutionalisation of Thaipusam in Southeast Asia coincided with the establishment of urban Murugan temples by affluent Chettiar merchants and the influx of indentured and kangani-recruited plantation workers.

In Malaysia, the Sri Subramaniar Temple at Batu Caves, Selangor, founded in 1891 by K. Thamboosamy Pillai, became the focal point for Thaipoosam. The earliest documented chariot procession carrying the vel from Kuala Lumpur to Batu Caves occurred in 1892, with kavadi devotees following shortly thereafter. By the 1920s, the festival had assumed its contemporary form: hundreds of thousands of devotees ascending the 272 steps, bearing ornate kavadis, and performing rituals. It grew into one of the world’s largest annual Hindu gatherings, regularly attracting up to 2 million participants before the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Malaysia, the Sri Subramaniar Temple at Batu Caves, Selangor, founded in 1891 by K. Thamboosamy Pillai, became the focal point for Thaipoosam. The earliest documented chariot procession carrying the vel from Kuala Lumpur to Batu Caves occurred in 1892, with kavadi devotees following shortly thereafter. By the 1920s, the festival had assumed its contemporary form: hundreds of thousands of devotees ascending the 272 steps, bearing ornate kavadis, and performing rituals. It grew into one of the world’s largest annual Hindu gatherings, regularly attracting up to 2 million participants before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Singapore’s Thaipusam procession originated even earlier. The Sri Thendayuthapani Temple or Chettiars’ Temple on Tank Road, consecrated in 1859, and the Sri Srinivasa Perumal Temple in Serangoon Road that was rebuilt in 1855–1861, jointly organised processions from at least the 1870s. Until the late twentieth century, devotees carried spiked kavadis weighing over 80 kg and inserted long spears through their cheeks.

Penang’s Waterfall Hill Arulmigu Balathandayuthapani Temple (consecrated 1850, relocated to hilltop 1930) developed a parallel tradition that today rivals Batu Caves in scale. Smaller but significant observances also emerged in Ipoh, Johor Bahru, and among Tamil communities in Thailand and Medan, Indonesia.

Sri Rama Tradition connects Ayodhya in India and Ayutthaya in Thailand

The historical and cultural interconnections between India and Southeast Asia are rooted in the shared reverence for the Rama and Ramayana. Ramayana story has traveled across the world through various art forms like paintings, music, dance, drama and storytelling. It has been the carrier of culture from India to the world. A particularly striking example of this diffusion is the linkage between Ayodhya, the birthplace of Sri Rama in India, and Ayutthaya, the former capital of the Kingdom of Siam now called Thailand. Founded in 1350 by King U Thong, also known as Ramathibodi I, Ayutthaya served as a thriving cosmopolitan center until its destruction by Burmese forces in 1767.

The city’s name, deliberately derived from “Ayodhya,” underscores a deliberate invocation of Sri Rama’s kingdom to inspire royal authority based on his Ram Rajya – the perfect state where no one is diseased, depressed or lives in fear. Sri Ram is an archetype of divine kingship that kings inspire to emulate. Indian cultural elements came to Siam via trade and migration since the first millennium CE, over time they were adapted into local contexts. For example, the Ramayana evolved into the Ramakien, a national epic that permeates Thai literature, performing arts such as khon dance-drama, and visual iconography. The adoption of “Rama” as a regnal title by Thai monarchs, beginning with the Ayutthaya period and continuing through the Rattanakosin era. It positions these rulers as symbolic descendants or avatars of Sri Rama, thereby intertwining political legitimacy with the epic’s ethical framework.

Architecturally and spatially, Ayutthaya mirrored aspects of Ayodhya’s idealized form. Spanning over 140 square kilometers with an intricate system of canals, temples, and palaces, the city integrated Khmer, Sukhothai, and Indian influences, creating a landscape that evoked the grandeur of Rama’s domain. Key sites, such as Wat Phra Si Sanphet and Wat Mahathat—now part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site—feature motifs from the Ramayana, including depictions of Rama’s battles and alliances

Contemporary manifestations of this linkage further strengthen the enduring Rama tradition. In a symbolic gesture during the construction of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya, inaugurated in 2024, soil from Ayutthaya and water from Thai rivers were incorporated into the temple’s foundation, reinforcing the spiritual bond between the two sites separated by approximately 3,500 kilometers. Such exchanges not only preserve historical ties but also foster modern diplomatic and cultural relations between India and Thailand.

The Global Diaspora of Jagannath Worship

The worship of Sri Jagannath is deeply rooted in the cultural and religious fabric of Odisha. The iconic Jagannath Temple in Puri dates back to at least the 12th century CE in structure and much longer in tradition. The establishment of new Jagannath temples abroad reflects the diaspora’s efforts to maintain spiritual continuity amid displacement and cultural adaptation. These temples replicate ritualistic elements—such as the three Murtis of Jagannath, Balabhadra, and Subhadra at the core of the temple and annual rituals like Rath Yatra.

Earliest Jagannath temples beyond India’s modern borders are those in neighboring countries that were a part of India before 1947. These include Comilla Jagannath Temple, also known as Sateroratna Mandir, in Bangladesh built by King Ratna Manikya II of Tripura in 18th CE, though with possible origins in the 16th century. Handial Jagannath Mandir in Bangladesh’s Handial village dates between 1300 and 1400 CE.

Earliest Jagannath temples beyond India’s modern borders are those in neighboring countries that were a part of India before 1947. These include Comilla Jagannath Temple, also known as Sateroratna Mandir, in Bangladesh built by King Ratna Manikya II of Tripura in 18th CE, though with possible origins in the 16th century. Handial Jagannath Mandir in Bangladesh’s Handial village dates between 1300 and 1400 CE.

In Pakistan, the Jagannath Mandir in Sialkot’s Kashmiri Mohalla was built around 1953, after the 1947 Partition. Despite incidents of vandalism and theft it remains operational.

The early 20th century witnessed the emergence of Jagannath temples in regions shaped by British colonial indentured labor systems, particularly in Africa and the Indian Ocean. The Shri Jagannath Puri Temple in Tongaat, South Africa, was established in 1900 by an Indian immigrant family, mirroring aspects of the Puri temple amid apartheid-era constraints on non-white land ownership. This construction reflects the diaspora’s adaptive strategies in maintaining cultural identity under oppressive regimes.

In Mauritius, the Shri Jagannath Temple in Sibal was founded in 1933 and is now managed by ISKCON. Serving a Hindu population largely descended from indentured laborers, it hosts vibrant Rath Yatra.

The latter half of the 20th century marked a surge in Jagannath temples globally, propelled by ISKCON’s efforts. These include Jagannath temples in London, Moscow, San Francisco, Australia, Italy, Brazil, Canada.

The Shri Jagannath Temple in Chicago, initially established in 2008 at the Bishnu Shiva Shakti Temple in Aurora, Illinois and relocated to Elgin in 2014 was built by the local Odia community. It carries forward the tradition of Anna Dana just like the Puri temple.

Jagannath temples outside India underscore the diaspora’s devotion and agency in cultural preservation.

Swaminarayan Temples around the World

The Swaminarayan Sampradaya, founded by Bhagwan Swaminarayan (1781–1830) in Gujarat, has expanded globally through migration and organizational growth, leading to the construction of numerous temples abroad. As of 2025, over 1,000 Swaminarayan temples exist worldwide, with BAPS operating more than 1,300 mandirs and centers, many outside India.

The earliest Swaminarayan temples abroad emerged in East Africa, driven by Indian indentured laborers and traders under British colonial rule. These structures often started as modest assembly halls before evolving into full mandirs. Notable among these are the two temples in Nairobi Kenya built in 1945 and 1954, two in Mombasa Kenya in 1955 and 1958, Dar-e-salaam Tanzania in 1958.These African temples reflect the sect’s adaptation to colonial challenges, providing spiritual anchors for migrants through satsang activities.

The earliest Swaminarayan temples abroad emerged in East Africa, driven by Indian indentured laborers and traders under British colonial rule. These structures often started as modest assembly halls before evolving into full mandirs. Notable among these are the two temples in Nairobi Kenya built in 1945 and 1954, two in Mombasa Kenya in 1955 and 1958, Dar-e-salaam Tanzania in 1958.These African temples reflect the sect’s adaptation to colonial challenges, providing spiritual anchors for migrants through satsang activities.

The 1960s–1980s saw accelerated construction as Swaminarayan followers spread to the UK, North America, and beyond following decolonization and economic migrations. Late 20th and Early 21st-Century Swaminarayan temples saw global proliferation with grand Shikharbaddha mandirs and monumental Akshardham complexes blending devotion with cultural education. This includes the much publicised temples at New Jersey and Abu Dhabi.

Expansion of these temples tells us about the economic prosperity of the diaspora building these grand temples as they make their culture visibly a part of their chosen new homes.

Sharada Peetha – Contemporary Revival in Kashmir

Sharada Peetha is a pivotal symbol of ancient Hindu scholarship and devotion in the Kashmir region, dedicated to Devi Sharada — the goddess of knowledge, wisdom, and artistic pursuits. It is one of the 18 Maha Shakti Peethas dating back to at least 5,000 years. It was a premier center of learning, a university that drew intellectuals from across the regions to study philosophy, grammar, logic, and metaphysics. It was home to Kashmir Shaivism, a non-dualistic philosophical tradition within Hinduism. The name also indicates the Sharada script. Adi Shankaracharya traveled to Sharada Peetha, engaging in scholarly debates and ascending the “Sarvajna Peetha,” or throne of omniscience, which marked a milestone in his doctrinal campaigns.

Following the 1947 partition of India, Sharada Peetha resides in the village of Sharada within the Neelum Valley of Pakistan occupied Kashmir, close to the Line of Control delineating Indian and Pakistani territories. This location’s inaccessibility to Indian pilgrims has led them to build a new Sharada Peetha very close to the original but inside the Indian borders at Teetwal that was originally called Teerthabal, on the banks of Krishna Ganga, in the Kupwara district of northern Kashmir.

This initiative is an endeavor to continue the religious practices and cultural identity of Sharada Peetha by offering an alternative venue for pilgrimage and worship devoid of cross-border impediments.

The temple was inaugurated in March 2023, on Navreh—the Kashmiri New Year and the commencement of Navaratri. The temple enshrines a Murti from Sringeri Math in Karnataka crafted from stone with traditional Kashmiri motifs. Teetwal temple facilitates teertha yatras and fosters a renewed connection for Kashmiri Hindus with their ancestral roots. Teetwal reconstruction heralds a paradigm of adaptive continuity, bridging antiquity with realities of the times.

Conclusion

Teerthas get recreated to have the energy of the sacred tirtha close to you which may be physically away from you due to migration or changing political boundaries. They keep the pilgrims deeply connected via the alternate while they still yearn for the original.

Documenting the replicated Teerthas and temples across would be documented the cultural journey of the Indian diaspora.

References

- Gossagne Napal, G. (2008 reprint of 1927 account). History of Ganga Talao. Mauritius: self-published.

- Jhurry, R. (1995). Ganga Talao: The Sacred Lake. Port Louis: Mahatma Gandhi Institute Press.

- Central Statistics Office, Mauritius (2022). 2022 Housing and Population Census – Religion. https://statsmauritius.govmu.org/Pages/Statistics/ESI/Population/2022/Popaspx

- Soobarah, N. (2018). “Maha Shivaratri Pilgrimage in Mauritius: Tradition and Transformation.” Journal of Mauritian Studies, 7(1), 45–68.

- Belle, C. (2015). Thaipusam in Malaysia: A Hindu festival misunderstood? [PhD thesis]. National University of Singapore.

- Pillai, K. T. (1962). History of the Sri Subramaniar Temple, Batu Caves. Batu Caves Temple Committee.

- Yeoh, S. G., & Kong, L. (2012). Singapore’s Indian landscapes: Religion and ethnicity. In T. Oakes & C. Sutton (Eds.), Faith in the city (pp. 87–108). Routledge.

- https://sahistory.org.za/place/shri-jagannath-puri-temple-tongaat

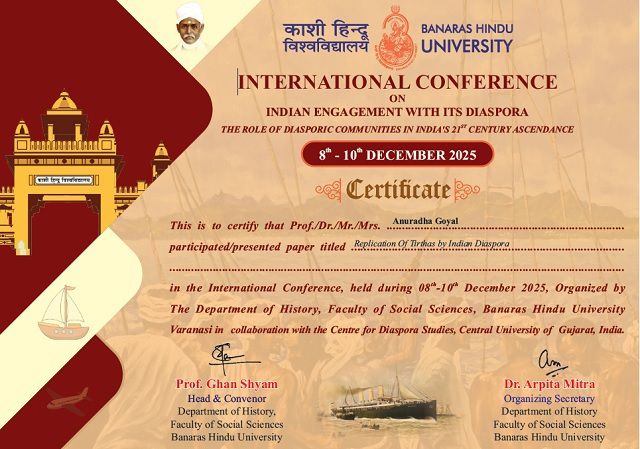

This paper was presented at The International Conference on Indian Engagement With Diaspora organized by Department of History, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi on 8-10 Dec, 2025.

A very detailed description of the Sanātani footprint across the globe, which I wasn’t aware of until now. Thank you for this. 🙏

I possible please share links of this nature.

Thank you.